Eretria: Insights into an Ancient City

Austerity is not the only show in Athens. In antiquity, Greek city-states sometimes passed laws to limit conspicuous consumption, but they still made and patronised the most beautiful items in many areas of their lives. Athens’ National Archaeological Museum is hosting a magnificent exhibition of almost 450 items from the ancient site of Eretria, a co-production with the Swiss School of Archaeology, excavators at Eretria for almost 50 years.

The dominant image of ancient Greek art is still based on great items found in Athens, with a southward look to that polar opposite, Sparta. Sensational finds in northern Greece, in Philip and Alexander’s Macedon, have recently widened our knowledge, especially of painting and gold and ivory work, but items from the scores of other Greek city-states are less well known. This important exhibition establishes Eretria, a city on the island of Euboea, as the site where a continuity of more than a thousand years can be brilliantly displayed: I have never seen a show that better illustrates so many sides of Greek culture across such a time span. It is a presentational triumph.

Where was ancient Eretria? One of two important cities on Euboea, the country’s second-largest island after Crete, it looked west across a narrow channel to the nearby coast of north-east Attica. Its sophistication and influence were such that its culture can claim to lie at the origins of western civilisation, an argument that rests on a Euboean ancestry for the Roman alphabet used today.

In the Athens exhibition, a well-captioned case shows the very latest Eretrian contributors to this theory. They are simple bits of pottery, found in a sanctuary on the site, inscribed with lettering in the 8th-century BC. Fascinatingly, they show an intermediate phase of writing in which non-Greek words are written in Greek script and non-Greek letter-forms are also present. These mixed signs are crucial evidence that contact between a Semitic script in the Near East and Euboea’s Eretrians was the vital link in the birth of the Greek alphabet.

The 8th-century BC is the era at which Eretria is most fascinating. The show does it justice, explaining the site’s new settlement, displaying its painted pottery and relating it to the remarkable finds at nearby Lefkandi. On show are some of the gold and grave-goods that recently exploded old ideas of a long Greek “dark age”. They include clay figures of fabulous centaurs, which rank as the first material evidence for Greek myths in this “dark” period, the formative age for Homer’s poetic predecessors. Eretria then adds the archaeologists’ latest surprise, a big ceramic mixing-bowl for wine on which a sexually aroused stallion is shown mounted on a mare, an unparalleled image on such an object. On the other side of the bowl two horses, similarly occupied, are accompanied by a puzzling image which is thought to show a taller and smaller human figure, apparently engaged in a less direct sort of sexual activity. It looks as if the humans are both males, the smaller one a boy. It seems likely that this bowl was illustrated so as to be fun for male guests to look at during their drinking parties. In the Athens museum, the side with the human figures is discreetly turned away from the viewer, but the accompanying captions set out the evidence.

If sex and scripts fail to catch your interest, the Eretrians’ archaic Greek sculpture will take over. The decoration of their great temple of Apollo is explained with a neat use of digital technology, filling out the surviving fragments and then appearing to toss them up to their original position on a mock-up of the temple’s pediment. The temple was destroyed by Persian invaders in 490BC but one of the magnificent sculpted Amazons survived and has returned from Rome to Athens for this show. It was taken from Eretria in ancient times and brought to Rome by antiquities looters and had not been back to Greece since then.

Eretria is a site known especially for finds of well-designed houses. They contribute here to displays that cleverly show domestic activities and the lives of women and children, captioned with details that even expert historians need to take on board. Religious cults, textile-working, the gym and drinking parties are among the subjects of thematic displays that bring the city’s lifestyle clearly before us. They are accentuated by fine mosaic floors and a dense array of small sculptures and figurines, made from the 4th-century BC onwards. Among these, and part of a cache of marble figures unearthed by Swiss archeologists, is a young Eros holding up his face for a kiss from his mother Aphrodite, goddess of love. Both are divinely naked and while she embraces him in her left arm, his wings, clearly shown, are folded at rest on his back.

The Greeks continue to spring such lovely surprises, ever beautiful in their smallest details. Ancient and unique, they are an encouraging counterpoint to the country’s present crisis.

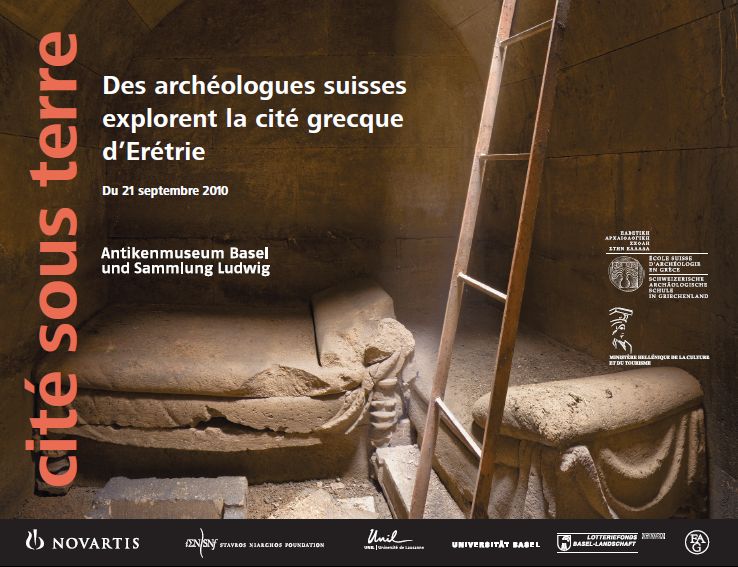

Until August 24 at the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, www.namuseum.gr, and then at Antikenmuseum, Basel, September 22-January 30 2011, www.antikenmuseumbasel.ch

By Robin Lane Fox

Published in the Financial Times, June 3 2010