The development of the Artemision

The exploration of the Artemision at Amarynthos results from a close collaboration between the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece (ESAG) and the Ephorate of Antiquities of Euboea (EAE). On the basis of a new collaboration protocol, the project is currently directed by Sylvian Fachard, Director of ESAG, and Angeliki Simosi, Director of the EAE.

The ongoing research project (2021-2025), supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) and the State Secretariat for Education, Research and Education (SERI), aims to study the origin and long-term evolution of the Artemision and its contribution to the making of Eretria’s sacred landscape. It relies on three research axes: 1) a survey of the sanctuary’s territory and the sacred road between Eretria and the Artemision (directed by Sylvian Fachard), 2) a reappraisal of the site occupation in the Bronze Age (directed by Tobias Krapf), and 3) the excavation of the Geometric and Archaic remains in the Artemision with a comparative study of the ritual practices performed in the Eretrian places of worship (directed by Samuel Verdan and Thierry Theurillat). Fieldwork is co-directed by Tobias Krapf, Scientific secretary of ESAG, Tamara Saggini, FNS-ESAG collaborator in charge of the temple’s excavation, and Olga Kyriazi, archaeologist at the EAE.

Environment

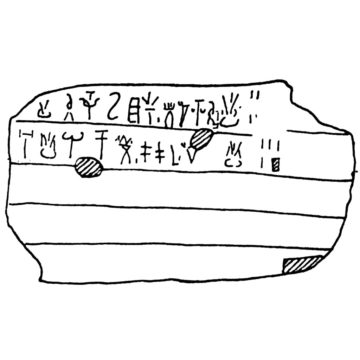

The Paleoekklisies hill is a coastal eminence that occupies the eastern edge of the Sarandapotamos river drainage basin, probably called the Erasinos in Antiquity.

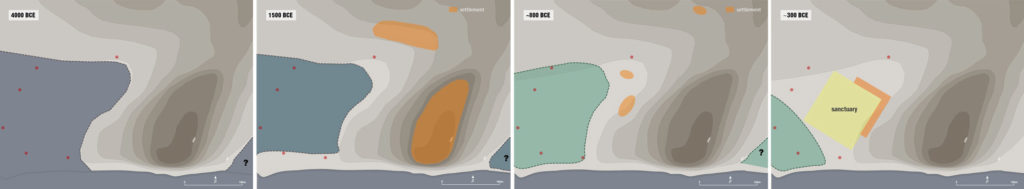

Thanks to a geoarchaeological project in collaboration with the French CNRS-CEREGE directed by Matthieu Ghilardi, the paleoenvironment of the Artemision can be reconstructed and shows significant change since Antiquity. From the Early Holocene to c. 2,600−2,400 BCE, the area was characterized by a fully marine environment. The latter then developed into a brackish/closed lagoon from the Early Helladic to the Late Geometric period (c. 750 BCE), mostly due to the deltaic progradation of the Sarandapotamos river. From the end of the eighth century BCE onwards, the lagoon was progressively replaced by swamps. The Sanctuary then developed in a constraint environment, in between coastal marshes to the west, a rugged promontory to the east, and the sea shore to the south. Such a landscape is typical of the setting of other sanctuaries of Artemis lying along the Euripus Strait and further south at Brauron, Halai, Aulis and Istiaia.

Archaeological plan

Amarynthos, archaeological plan (2021)

Amarynthos, archaeological plan (2021)

The Bronze Age

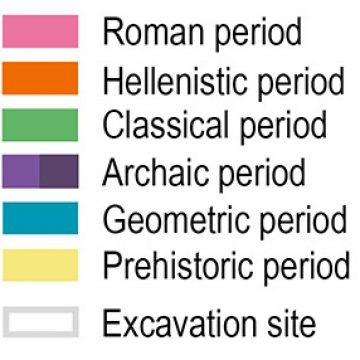

The topographical setting of this coastal hill is typical of the region’s Bronze Age sites and shares many parallels with Drosia, Dramesi, and Lefkandi. The latter, in particular, bears close similarities to Paleoekklisies, with its two anchorages (now silted up) behind the tell. Architectural features belonging to all Bronze Age phases have been excavated on top of the hill by the Greek archaeological service in the 1980s. A Middle Bronze Age settlement was also partially excavated north of the hill, which indicates that the site extended beyond the confines of the tell around the prehistoric lagoon. Mycenaean figurines, human and animal, found in the slope deposits are too few to support early cult activity at the site. The finds, however, indicate the presence of a sizeable settlement, no doubt the only major Mycenaean site located between Aliveri and Lefkandi. This supports its identification with Late Bronze Age a-ma-ru-to, attested on a Linear B tablet and on an inscribed sealings from the Theban Kadmeia.

Further reading

Tobias Krapf, Ερέτρια και Αμάρυνθος: δυο γειτονικοί αλλά διαφορετικοί οικισμοί της Μέσης Εποχής Χαλκού στην Εύβοια. In A. Mazarakis Ainian (ed), 4ο Αρχαιολογικό Έργο Θεσσαλίας και Στερεάς Ελλάδας, Conference held in Volos (15.3-18.3.2012). Volos 2015, 681-696.

The Early Iron Age

Our knowledge of the transition to the Iron Age and the occupation of the early first millennium BCE on the site is still fragmentary. Early Iron Age remains are absent from the summit of Paleoekklisies hill, but discoveries made at the foot of the promontory show that the edge of the cove created by the Prehistoric bay was occupied between the Mycenaean and Geometric periods. The earliest evidence consist of a large wall from the 11th-10th century excavated under the foundations of the East Stoa and a child grave from the 9th century containing nine vases. The remains of absidal buildings dating from the 8th century have been partially excavated, which are reminiscent of similar structures in the sanctuary of Apollo Daphnephoros at Eretria.

Votive offerings from the eighth and early seventh centuries BCE have been discovered out of context in later backfills: fragments of bronze shields, a serpentine seal from the ‘Lyre Player Group’, as well as several graffiti inscribed on pottery and terracotta. A late 8th century BC bronze statuette of a bull was also discovered in a pit at the foot of the hill; it is reminiscent of examples from Peï Dokou near Chalkis and from the Kabirion of Thebes.

The Archaic period

The Archaic period saw the first monumentalisation of the sacred space. In the plain to the West, the massive foundations of a large building with an axial colonnade measuring more than 30m × 10m were uncovered. Oriented to the east and facing a 5m × 12m monumental foundation, it is identified as the temple of Artemis and its altar. A quiver, probably belonging to a statuette of Artemis, and a bronze butt-spike were discovered in the vicinity of the altar.

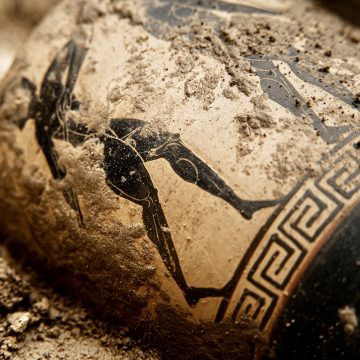

Excavation inside the building yielded a rich deposit of offerings including ceramic and bronze vessels, painted terracotta figurines, gold jewellery, silver, faience, glass and semi-precious stones, orientalizing seals in the shape of scarabs, as well as weapons (including a helmet and a shield). This deposit, dated to the last quarter of the 6th century BC, is probably linked to the construction of the temple.

The ongoing excavations have also revealed the existence of an earlier building with a mud-brick elevation and of a first altar facing it. This first temple probably dates back to the second half of the 7th century B.C.

Further east, a 38m long building was erected at the same time, with large doors at each end, allowing access to the sanctuary. In the centre, two spacious rooms open onto the sacred space. Their function remains unknown for the time being. Directly to the west, a shallow basin, whose walls and floor were made of large Corinthian tiles, was uncovered, suggesting water-related activities took place in front of the building.

A gravel roadway ran alongside the building, edged by a terrace wall. A pit situated between the roadway and the building contained a fragment of a small bronze wheel, which bears the name Θεογ− inscribed from right to left.

Further reading

Samuel Verdan et al., The early phases in the Artemision at Amarynthos in Euboea, Greece. In T.E. Cinquantaquattro – M. D’Acunto (eds), Euboica II. Pithekoussai and Euboea between East and West, che sarà pubblicato nella rivista AION, Annali di Archeologia e Storia Antica, Università degli Studi di Napoli L’Orientale, n.s. 27, 2021, 73-118.

The Classical period

In the course of the fifth century BCE, a tamped roadway (at least 3.5m wide) was built over its Archaic predecessor, following the same orientation and delimited on one side by a new rubble wall. Traces of wheel-ruts are preserved on its surface. In the first half of the fourth century, a rectangular building opening onto the west was built on the Classical roadway. Its plan, only preserved to the level of its foundations, measures 12×9m, with two bases meant to support semi-engaged pilasters separating the interior into two equal spaces. The building has been tentatively interpreted as a propylaion succeeding to the monumental Archaic edifice.

North of the sanctuary, scant remains belonging to an early portico have been uncovered, which was probably erected along an earlier temenos wall.

Three small quadrangular buildings aligned with the North portico face the altar, whereas a series of similar structures has been excavated south of the temple. Their plan is reminiscent of oikoi, buildings of various functions that are found in sanctuaries.

The Hellenistic porticoes

The most impressive discovery to date is an elongated two-aisled ‘π’ stoa, 11.80m in width and 69.20m in length. It overlies the earlier roadways and has a similar SW-NE orientation, thus maintaining the structured axis in place since the seventh century BCE. The northern wing is prolongated further to the north-west by a one-aisled stoa. Together the two porticoes border a large courtyard, maybe the aulè mentioned in the Eretrian law of the Artemisia (IG XII 9, 189).

Only a portion of the Eastern stoa has been excavated. The front colonnade rests on a foundation made of two courses of conglomerate blocks. The colonnade had a Doric entablature, attested by the discovery of a limestone frieze block with a three-metope span, as well as a fragment of the cornice. The stoa had a double-faced central colonnade with an intercolumniation of 5.20m. The overall plan is ordered according to a 5.20m module, probably the equivalent of 16 Doric feet, which regulates the inner colonnade as well as the depth of the two aisles. Most of the limestone colonnades or the entablature were probably consumed in a Medieval lime kiln built on the facade of the stoa. The back wall of the stoa consisted of a mud brick elevation on a dressed stone socle, made of two rows of orthostats averaging ½ ton. The floor of the stoa was made of beaten earth. Regarding the chronology of the stoa, the excavation of the foundation trenches provided a firm date in the second half of the fourth century BCE, probably in the third quarter.

In a second phase (third century BCE), a stone bench was added along the back wall of the stoa, whose foundation blocks only survive. A single limestone base and a fragment of support have been recovered. In its last phase (third century BCE), a door and a propylaion were added in the backwall of the building.

The ashlar building

A large esplanade was laid out east of the stoa, extending towards the foot of the Paleoekklisies hill. A building made of ashlar masonry was partially embedded into the hill and made accessible through a beaten earth ramp. The plan of the building remains unknown, as only the north and east walls have been excavated. The side (north) wall is 10.90m and 0.56m wide; an 22 meter-stretch of the back (east) wall is visible and continues towards the south. The back wall was supported by engaged pillars acting as internal and external buttresses, constructed to resist the lateral pressure of the soil. In spite of the pillars, however, the rear wall fell apart, and its blocks were scattered inside the building. Based on the position of the collapsed blocks on the beaten earth floor, the rear wall was at least 2.25m high in five courses. The isodomic blocks display a very high quality of craftsmanship. The monument, whose chronology in the Late Hellenistic period is uncertain, might have been an analemma, an exedra, or even a portico.

The courtyard and sacred well

The vast courtyard bordered by porticoes housed votive monuments, of which several bases survive. Few fragments of sculptures and inscriptions were found, most of them were probably recovered in late Antiquity. Fortunately, the fortuitous discovery of a well from the imperial period gives the rare opportunity to get a glimpse of some of the dedications that adorned the sanctuary. Indeed, this semi-buried structure was entirely built with reused stelae, bases and architectural members. This intriguing underground structure was accessible by two opposing flights of stairs. More than 160 bronze coins were found on the stairs and in the well, suggesting that the structure might have had a ritual function. According to the finds the well probably had a long period of use from the 1st century BC to the end of the 3rd century AD.

The end of the cult of Artemis

The last phases of the sanctuary are still poorly known. It served as a place of cult practice until the Imperial period, as evidenced by the use of the sacred well and the repair of several buildings, including the north portico. The buildings were probably dismantled towards the end of Antiquity. One or two centuries later, early Christian tombs testify to the symbolic force that the place still exercised.